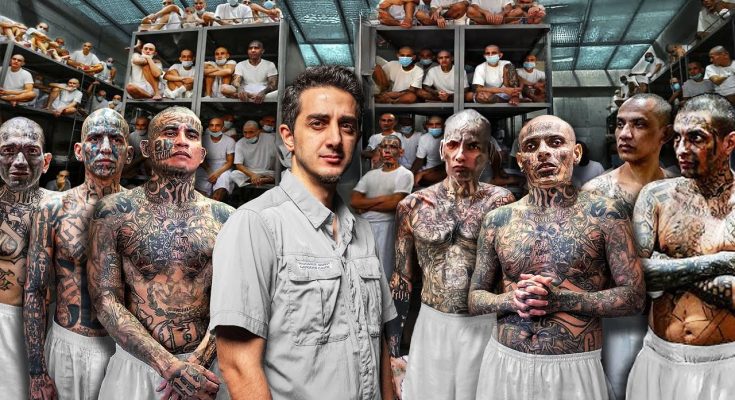

Introduction to CECOT: A Mega-Prison Like No Other

The Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT), located in Tecoluca, El Salvador, is one of the most infamous and largest prisons in the world. Opened in January 2023, this maximum-security facility was specifically designed to house some of the most dangerous criminals on Earth, including members of notorious gangs like MS-13 and Barrio 18. With a capacity to hold up to 40,000 inmates, CECOT has become a symbol of President Nayib Bukele’s aggressive crackdown on gang violence that once plagued El Salvador.

This prison is not just a facility for incarceration; it represents a broader strategy aimed at eliminating gang influence from society. However, its harsh conditions and controversial policies have drawn both praise and criticism globally. To understand why CECOT stands out as a unique institution, we must delve into its design, operations, and the political context surrounding its creation.

The Design and Security Features of CECOT

CECOT was purposefully built with extreme security measures to ensure that no inmate could escape or communicate with the outside world. The facility spans 410 acres of land, with the physical complex covering approximately 57 acres. It consists of eight massive cell blocks capable of holding thousands of prisoners each. The prison is surrounded by multiple layers of security:

- Electrified Fences: High-voltage fences encircle the perimeter.

- Guard Towers: Nineteen watchtowers staffed by armed guards provide constant surveillance.

- Gravel Flooring: Gravel around the facility ensures that any movement can be heard clearly.

- Advanced Surveillance Systems: CCTV cameras monitor every corner of the prison 24/7.

- Armed Personnel: Over 1,000 guards, soldiers, and police officers patrol the premises.

Inside each cell block are modules containing cells designed to hold between 80 and 100 inmates each—though overcrowding often results in more prisoners per cell. These cells are equipped with only basic necessities: metal bunks without mattresses stacked four levels high, two toilets, two washing basins controlled by guards outside the cells, and no personal items allowed.

For additional control over inmates’ behavior within CECOT, solitary confinement cells are used as punishment for those who violate prison rules. These isolation cells are completely dark except for a small hole in the ceiling that allows minimal light to enter.

Life Inside CECOT: Harsh Realities for Inmates

The daily life inside CECOT is marked by strict routines and minimal privileges. Prisoners spend almost all their time confined within their overcrowded cells—23.5 hours per day—with only a brief 30-minute window allowed for exercise or religious activities under heavy supervision in central hallways.

Meals provided to inmates are basic and repetitive: rice, beans, tortillas, plantains, and occasionally hard-boiled eggs or pastries—but no meat is served. Prisoners eat using their hands because utensils like forks or knives are considered potential weapons.

Inmates wear plain white uniforms consisting of shorts and shirts while their heads are shaved every five days as part of maintaining uniformity among prisoners. There are no educational programs or rehabilitation workshops offered within CECOT; instead, prisoners may engage in limited work such as fabric production under strict supervision.

Communication with family members or anyone outside is entirely prohibited—no phone calls or letters are allowed—and visits from loved ones do not occur at all.

Political Context: Bukele’s War on Gangs

CECOT was constructed during President Nayib Bukele’s state-of-emergency campaign against gang violence that began in March 2022 after an unprecedented spike in homicides attributed to criminal organizations like MS-13 and Barrio 18. Under this “state of exception,” constitutional rights were suspended to allow mass arrests without due process—a policy that led to over 84,000 people being detained by early 2025.

Bukele’s administration has framed this approach as necessary for transforming El Salvador from one of the most dangerous countries in the world into one of the safest nations in Latin America. Indeed, homicide rates have plummeted since these measures were implemented; however, critics argue that this success comes at significant human rights costs.

Human rights organizations such as Amnesty International have accused Bukele’s government of arbitrary arrests based on appearance or social background rather than concrete evidence of criminal activity. Reports also highlight cases where detainees died due to lack of medical care or alleged torture inside prisons like CECOT.

Global Reactions: Praise vs Criticism

While many Salvadorans support Bukele’s tough-on-crime policies—evidenced by his approval ratings exceeding 90%—international observers remain divided on whether facilities like CECOT represent justice or abuse.

Supporters argue that such measures were necessary given El Salvador’s history with gang violence controlling vast swaths of territory across the country before Bukele’s crackdown began in earnest. They point out that crime rates have dropped dramatically since these policies were enacted.

On the other hand, critics—including Human Rights Watch—describe facilities like CECOT as symbols of state violence replacing gang violence rather than addressing root causes such as poverty and inequality fueling criminal activity.

Conclusion: A Symbolic Yet Controversial Institution

CECOT stands as both a testament to President Nayib Bukele’s determination to eradicate gang influence from El Salvador and a lightning rod for debates about human rights violations versus public safety priorities. Its design ensures complete isolation for inmates deemed too dangerous for society while also raising questions about whether such harsh conditions align with principles of justice or rehabilitation.

As other nations observe El Salvador’s experiment with mega-prisons like CECOT—and even consider adopting similar strategies—the global community must grapple with balancing security needs against preserving fundamental human rights within incarceration systems worldwide.ShareSimplify